Saturday, June 30, 2012

On the Way to Tahiti

We left Fakarava yesterday (June 29) afternoon and are now in route to Tahiti with 110 miles left to go. Then it's the big city of Papeete (135,000) where we will have an internet connection for a longer post and photos. And I hear rumors of dark beer...

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Alive and Well in Fakarava

We are having so much fun here at the south pass of Fakarava that we seem to be having a hard time updating the blog. Or maybe swimming with sharks, lots of sharks, somehow affects the ability to write. Not to mention dolphins, turtles and the most amazing fish we have ever seen. And now we have to go get pizza with five or six other cruising boats. More to come.

Monday, June 11, 2012

Into the Tuamotu Archipelago

The atolls of the Tuamotus are as different from the islands of the Marquesas as aardvarks are to ice cream. (Well, YOU try to think of a better analogy than fish and bicycles.)

This is the main harbor at Ua Pou, our last stop in the Marquesas. Sockdolager

is anchored astern of the 84-foot cold-molded wooden gaff schooner Kaiulani, homeported in Hilo and San

Francisco. (Just look for the smallest boat.) We enjoyed spending time with

her owners and crew, and especially liked the fact that both boats were

designed by the same person: William

Crealock. Kaiulani, his largest one-off design, was his favorite, and the

Dana 24, his smallest, is arguably the most beloved.

This is a typical atoll in the Tuamotus. Where the Marquesas are craggy, jungle-y mountains at 9 degrees south latitude, the

Tuamotus, at 16 degrees south, are narrow rings of palm-fringed coralline sand

with immense reefs, surrounding 30 mile-wide turquoise lagoons. Max elevation is about six feet. The main attractions in the Tuamotus are

under the water’s surface, and this archipelago is one of the finest places

anywhere for diving and snorkeling. Look

up how atolls are formed. It’s

amazing to think they’re the tippety-tops of sunken volcanoes, with the lagoons

being where the craters once were.

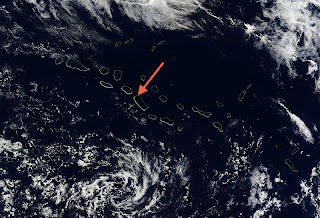

Our friend Marty From Prince Rupert asked us to please

identify exactly where we are next time we post, and also to look skyward and

wave so he could Google Earth us. Dude,

look at the arrow pointing to the northeast corner of Fakarava. Can you spot us?

Ua Pou was pleasant and we spent nearly a week there. The island’s jagged volcanic necks poked the

sky like spines on a dinosaur’s back, and clouds snaked around them. We saw several old friends at Ua Pou, and

made some new ones.

In spite of the calm, we managed to creep 35 miles, mostly

on a favorable current. Of course, Jim

tried to “purchase” some wind with cheap coins, which Neptune nearly tossed

back. Then he tossed in something

weightier: 100 francs. We can confidently report that 100 francs

will buy you 25 to 30 knots on the nose.

Which is why, while I was writing a blog post for the Ham radio, I had

to stop due to the need to cope with the weather, and all you got was that little 'we've arrived' blurb, before twelve-hour naps restored us. By now you should know that when you see one of those, it's safe to assume we do not want to be awakened.

Still learning to

sail the boat: We were entering the

archipelago, smack in between a small island called Tikei and two large atolls

called Takaroa and Takapoto. The wind

from a frontal system further west quickly came up from the south. The frontal system followed.

At first it was a nice reaching breeze, and in the draft I

wrote: “We are right on our rhumb line

and can see Tikei Island off to port, but cannot see two big atolls--Takaroa

and Takapoto—in our lee, off to starboard.

The wind's about 10 knots from the SSE, making this a beat to windward,

but the chop's not too big yet. The wind should ease east sometime in the next

day, too. Maybe 100 francs was just the

right amount of wind to buy after all. We're doing about 3 to 3.5 knots, and

there are 100 miles to go to Fakarava's north pass.”

Ha Ha Ha! The wind should ease! Good one.

Shortly after we began “coping,” the wind “eased” from 10 to 25 knots

with higher gusts (on the nose), and the light chop went to 6 to 10 foot seas closely

spaced, in darkness.

Thinking the double headsails were contributing to the lee

helm, we doused the genoa and went under staysail and double-reefed main. Several years ago in the Queen Charlottes, we

had easily sailed to windward in 30 to 40 knots of wind, but with no seas—we

were behind a rock reef in calm water back then, and it was amazing to see the

boat scoot like that. But in these big

seas between atolls, the helm was alarmingly mushy as the seas stopped us cold. Sockdolager

couldn’t regain momentum in time to weather the next wave because they were so

close together. There was so much lee

helm that we actually checked over the side with a flashlight to see if we’d

snagged something and were dragging it.

We hadn’t. We just couldn’t sail

to windward anymore in that mess using our normal rig for that wind speed.

Every boat has its point of wind speed and wave size where

it will no longer be able to sail to windward, and we reached ours under this

particular sail combination (double-reefed main and staysail) at about 25 knots

and 6 to 10 foot seas closely spaced.

Though it was no picnic, it wasn’t out of control—just uncomfortable.

Finally, we realized what was actually happening. Because it was the first time we’d bumped

these limits, the normally sensible strategy of reefing to lessen heeling and

increase speed did not seem flawed at the time, but it was. When seas knock you into immobility and you

need to get to windward, you may need more, not less sail, or you won’t recover

your momentum after each wave. I suppose

if the waves had spread out further, or grown larger so that we could climb

them like hills instead of being slapped, our ability to sail to windward might

have improved.

Options: One strategy was to give up on Fakarava and

run a hundred miles off the wind to Ahe or Manihi atoll, but we didn’t like

that idea. Another option was to resume

our original sail configuration, which would have allowed us to punch into the

weather, but at the cost of being severely over-canvassed. In an emergency this is what would have to be

done, but it wasn’t an emergency, because we had 12 miles of sea-room and other

options for not drifting down on the reefs.

A third option was to use the engine.

Results: We motorsailed upwind, back to our rhumb line

between the atolls. A couple gallons of

diesel worked like a charm, and we’ll still have enough to explore Fakarava and

later, get into harbor at Tahiti. Soon

we were in the lee of Kauehi atoll, just a couple miles offshore, and the seas

subsided. I should say that the boat did

magnificently under the circumstances, which forced us to learn the upwind

limits of a 21-foot waterline in that particular wind and wave signature. Larger boats might have larger limits

depending on design, but usually a longer waterline can punch through more that

a short one. We also know we could have

sailed out of there if we’d had no engine.

It reminds me of the story by Cap’n Fatty Goodlander, of having to

deliberately over-canvas his boat to claw off a lee shore near Madagascar in

hellatious seas. Now we truly understand

why he had to do that.

In that interrupted draft I also wrote: “It's weird moving

into a huge area of coral atolls and low sand islands that mostly can't be seen

until you're close enough to see the tops of palm trees, just a couple miles at

best. And it's easy to see why they got

their fearsome reputation as the "Dangerous Archipelago" in pre-GPS

days. Without the GPS we'd be taking the

more open northern route, as many cruising boats did when celestial navigation

was the only option. Plus, currents can

run hard around the atolls, not just in the passes.”

So it’s dark and windy, and the moon won’t rise until

midnight, and we’re threading through a maze of atolls. With a turn to put the wind finally aft of

abeam, plus an alert lookout, GPS and a backup position plot on the paper chart

every couple of hours, it’s just tiring rather than difficult. The rest of the sail to Fakarava was pretty

decent, and at 4:00 am we hove-to off the North Pass, waiting for daylight and

slack tide at 7:30. We’re happily anchored

off the village in the northeast corner, but will head for the famous South

Pass in a few days.

What REALLY gets a

sailor’s goat:

Actually, it’s the calms.

In spite of the excitement of the between-atoll sail, being becalmed can

still be the most difficult, especially when a swell is running.

Witness our friends Patrick and Kirsten aboard Silhouette, a Cabo Rico 38 currently enroute from the

Galapagos to the Marquesas. We keep in

touch via email over the Ham radio, and they actually download our blog posts as a stay-awake aid on dark night

watches. Whoa—someone please tell them

about iPods and headphones!

Patrick wrote rapturously about days and days of gorgeous

trade wind sailing (which made us green with envy), but it was shortly followed

by this: “Okay, I knew it would happen,

but I sent you that note anyway. You know, the one about the marvelous trade

wind sailing we had been experiencing for the past 17 days. Well it went away.

The wind started dropping last night and it stayed that way all day today. We

tried running wing & wing and eventually got the asymmetrical spinnaker

out. Soon it was hanging limp as well. Not wanting to waste the moment I

returned to re-read one of Karen's latest posts... The one about waiting for

wind and how character building it is. I

added the character building part by reading between the lines.”

Hoo boy, now WAIT JUST A GOL-DURNED MINUTE! I wish to make it exquisitely clear that had

we carried enough fuel, we would have FLOORED IT and gotten the heck out of the

ITCZ and across the Pacific, too! But

upon re-reading the lines, the character-building implications did kinda leak

through, didn’t they. Oh well.

Patrick continued: “So

after due thought and careful consideration I did what every Puget Sound sailor

would do, I turned the key and "Vroom, the diesel rumbles to life..."

and off we went. Do I feel bad? Well I did at first, but thus far on this passage,

we had hardly used any fuel since leaving the Galapagos. In fact we had to this

point only run the engine for motive power a bit getting out of the harbor and

clear of the land and the balance to charge batteries when the cloudy days

prevented the solar panels from keeping up. We had spent the past 17 days

actually sailing, day in and day out. What to do, what to do? I didn't want to

let Karen down! OK, I've got it. I

realized the batteries hadn't really had a "full charge" in over two

weeks so I'm doing it for them. That's my story and I'm sticking to it. My

conscience feels clear already.”

Ahh, we thought, he is wrestling with monumental stuff

here. Rationalization is a perfectly

good tool for that.

But then ANOTHER note:

“Barely an hour after confessing to Sister Karen that I was weak and had

succumbed to the Siren call of the diesel, the wind returned. Not to its former

level, but usable. Using it we are, even though the batteries aren't fully

charged. Bless you, Sister.”

You are forgiven for your brief lapse, Brother Patrick. The Church of the Becalmed and Pretending to

Love It welcomes you.

The Tuamotu Tutu: Seriously, wouldn’t that make a great

song? And speaking of churches, there

was quite the parade here in town yesterday.

The entire town came out for it, and all of us yachties

joined in, too. Turns out the Catholic

priest (and isn’t that a lovely church?) told his flock that instead of

spending Sunday afternoons online ordering Costco goodies, they should all be out

making a joyful noise. They took him up

on it.

Leading the parade was this truckload of smiling drummers,

followed by a truckload of guitar players whom no one could hear because the

drummers were so loud. They drove down

to a crowd of about a hundred fifty people led by a white and gold phalanx of

priests, with children scattering flowers from palm baskets along the path in

front of the procession.

There were some very good and enthusiastic singers in that

group, and it was a joy to listen and sing along—though my efforts probably

sounded like a two year-old’s version of their language. They were having a lot of fun. The next altar, the same thing. We realized that these altars were probably

like stations of the cross, of which there are a LOT to be spending 15 minutes

at apiece, so after the third round we and our buddies Don and Deb from Buena Vista walked back to the

dinghy to spend the evening together on Sockdolager,

making our own joyful, Margarita-fueled noise.

Here are Deb and Don Robertson and Karen, trying but not quite succeeding, to behave in church.

Here’s a sweet little Tuamotan cottage.

We’ll relax here a bit more after the passage, then will

head for Fakarava’s South Pass, where all those cute little sharks live.

Sunday, June 10, 2012

Safe in the Tuamotus

We arrived in Fakarava Saturday morning after a good seven day passage of 560 miles from the Marquesas. All is well, more soon.

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Chasing the Sun (and Wind)

After all these years, I've realized something about sailing that's very obvious, but at a far deeper level: you spend an awful lot of time waiting for wind. Back on Puget Sound where diesel was sold at every corner marina, it was not as noticeable a dilemma when the wind failed (as it often does) because you could get there just as fast--sometimes faster--with the turn of a key. Vroom, the diesel rumbles to life, dissolving any pretensions that you really, truly wanted to sail the whole way. The choice is whether to disturb the peace for convenience's sake, or to sit tight and wait for wind. If we were in Puget Sound in a calm, it's likely we'd start the engine, especially if no wind was in the forecast. But we've read in multiple accounts that in the Tuamotus, diesel is unavailable. We are now becalmed and have been for several hours, drifting at one knot on the current. So the choice is: do we want to wait for wind, in hopes the calm's short-lived (the wait possibly being measured in days), or go for it and use our precious diesel?

News flash: As I write this, Jim is attempting to PURCHASE some wind. He's dropping seven Polynesian francs overboard. He also wants to see how fast they sink. The trick with this method is to not buy too much wind. Uh-oh. He just came back down, saying, "These cheap coins actually float a little, and I can't tell how fast they're sinking before we drift away from them. I need a heavier coin." He just dropped a 100 franc coin into the drink. That's a whole dollar, fer cryin' out loud. Heaven help us, we may have bought a gale.

A mega-sailing yacht passed us two evenings ago, just before sunset. We were enjoying a nice reach of 4 to 5 knots. The mega-yacht was motoring downwind with just a staysail up, doing 11 knots. There was a perfectly usable breeze blowing. Just to say hello, I picked up the VHF radio mic and called the mega-yacht, which looked at least a hundred feet long and had a very tall and empty mast. At sea, mariners are as equals, and big ships talk to tiny sailboats. The voice answering sounded very formal but friendly, and had a Scottish accent. I said, "We're watching your speed and envying you for that."

"We carry and use a lot of diesel," he admitted, but we go around the world on the owner's behalf, chasing the sun." They were going to Fakarava Atoll, too, then Tahiti. He said, "We'll be there tomorrow around noon, and will look for your arrival. What's your ETA?" (estimated time of arrival.)

"Oh, maybe four days," I said. "We carry 20 gallons of diesel and have a 21-foot waterline."

"Wow, then you must do a lot of sailing," he said.

"Indeed we do."

We're still becalmed. Who knows what ETA we'll have? We'll get there when we get there. But it's 90 degrees inside the cabin, and getting our 21st Century selves moving via iron genoa and its artificial breeze while enjoying a cool drink sounds pretty darned fine compared to roasting under the noonday sun, listening to slatting sails, and going nowhere. So why must we always be moving? That old journey-as-destination question again, and still no answers.

We just had a swim call. It's one of the bennies of a calm day at sea.

Patience is part of the bargain in sailing a small boat long distances. We're just as impatient as the next person, but every time we get becalmed we remind ourselves that we programmed it this way, sailing and living on a small boat with limitations that force us to use the wind. We can't have the motoring range of a 40-footer unless we went to extremes of fuel tankage, and then we'd have to give up other heavy items, like food or water. No thanks. We don't need to chase the sun, nor could we if we wanted to. The sun finds us. Now, about those cold drinks... we've got those!

Sent via Ham radio

News flash: As I write this, Jim is attempting to PURCHASE some wind. He's dropping seven Polynesian francs overboard. He also wants to see how fast they sink. The trick with this method is to not buy too much wind. Uh-oh. He just came back down, saying, "These cheap coins actually float a little, and I can't tell how fast they're sinking before we drift away from them. I need a heavier coin." He just dropped a 100 franc coin into the drink. That's a whole dollar, fer cryin' out loud. Heaven help us, we may have bought a gale.

A mega-sailing yacht passed us two evenings ago, just before sunset. We were enjoying a nice reach of 4 to 5 knots. The mega-yacht was motoring downwind with just a staysail up, doing 11 knots. There was a perfectly usable breeze blowing. Just to say hello, I picked up the VHF radio mic and called the mega-yacht, which looked at least a hundred feet long and had a very tall and empty mast. At sea, mariners are as equals, and big ships talk to tiny sailboats. The voice answering sounded very formal but friendly, and had a Scottish accent. I said, "We're watching your speed and envying you for that."

"We carry and use a lot of diesel," he admitted, but we go around the world on the owner's behalf, chasing the sun." They were going to Fakarava Atoll, too, then Tahiti. He said, "We'll be there tomorrow around noon, and will look for your arrival. What's your ETA?" (estimated time of arrival.)

"Oh, maybe four days," I said. "We carry 20 gallons of diesel and have a 21-foot waterline."

"Wow, then you must do a lot of sailing," he said.

"Indeed we do."

We're still becalmed. Who knows what ETA we'll have? We'll get there when we get there. But it's 90 degrees inside the cabin, and getting our 21st Century selves moving via iron genoa and its artificial breeze while enjoying a cool drink sounds pretty darned fine compared to roasting under the noonday sun, listening to slatting sails, and going nowhere. So why must we always be moving? That old journey-as-destination question again, and still no answers.

We just had a swim call. It's one of the bennies of a calm day at sea.

Patience is part of the bargain in sailing a small boat long distances. We're just as impatient as the next person, but every time we get becalmed we remind ourselves that we programmed it this way, sailing and living on a small boat with limitations that force us to use the wind. We can't have the motoring range of a 40-footer unless we went to extremes of fuel tankage, and then we'd have to give up other heavy items, like food or water. No thanks. We don't need to chase the sun, nor could we if we wanted to. The sun finds us. Now, about those cold drinks... we've got those!

Sent via Ham radio

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

Passage to the Tuamotu Archipelago

We're at sea, two-thirds of the way between the Marquesas and Tuamotu Archipelago. Our destination is the north pass of Fakarava Atoll. The Tuamotus are famous for riproaring tidal currents of 6 to 9 knots in the entrance passes. That and the fact that most of the archipelago's real estate is submerged reefs make these atolls worthy of very careful navigation. If we arrive at the pass during darkness or when the current's ripping, we'll have to sail back and forth for a few hours outside until it subsides. A bunch of our sailing buddies are hanging out at Fakarava's south pass, a place where, we're told, hordes of friendly sharks let you swim with them. Two adjectives about sharks in that sentence: hordes and friendly, just don't match anything my brain can yet accept, but so far none of our friends who've been there diving every day have reported any missing limbs. I once believed a story about a purple shark. Maybe such things as friendly sharks exist. Sure they do. Heeeere, leetle tourist!

A sea passage is like a slice of life; sometimes it sucks, other times it's glorious. We've had two nights of squally sideways rain and two days of perfect trade wind sailing. At the moment it's a post-card perfection of 4 to 6 knots downwind. As before on passage, Jim and I are like ships in the night, sleeping and standing watches 4 hours on and 4 off. There's plenty of time to think. Passagemaking isn't always fun; in fact it's more often tiring and difficult. At least most of our passages so far have been tiring and at times quite difficult. But it forces you into the present tense, as I've said before. Somehow the boat's ceaseless motion manages to toss out all the extraneous noise and clutter in my mind, the endless loops of critique, opinion and perspective, stuff that keeps me out of the singular newness of the current moment. Around day 3 it's just me and my internal terrain contemplating sky-blue questions on a spectacular morning that makes the tiresome night squalls fade like bad dreams. It's hard to find this state of mind so quickly anywhere else.

The at-sea visual: a maritime color palette with as many blues as Ireland has greens; The tactile: a cool breeze on the skin, to be savored before it melts into the day's heat; The memory: wondering what friends are doing right this minute and wishing I could call them; The amazement: look at how well this little champ of a boat is sailing!

We needed a real trade wind passage to restore our faith that it's not always a matter of tooth-and-claw for every mile gained, which was how the crossing of the Pacific felt far too often. So far, this passage is delivering on the promise. Our trade wind sail rig is a combination of reefed mainsail let way out and held with a preventer, plus staysail sheeted in fairly tight, and genoa. Right now the genoa is poled out to windward, but we also use it in standard configuration when broad or beam-reaching, both of which we've done on this passage. The great thing about this arrangement is that when a squall hits you just reef or roll in the genoa like a windowshade, leaving the staysail to give the boat power forward. It has worked so well we often haven't had to adjust the steering vane, either. We've toyed with the idea of poling the staysail out to leeward, but it seems to be playing an anti-roll function when sheeted in tight, and neither of the other sails is affected by its presence in the middle.

At times like this I get one of those Holy Crap, willya look at this! moments. I stare at the sails, the rig, the wind vane, the sparkling sea; I think back to all the preparation and hard work to make this happen, and then it hits me with a big smile: It's working! Just as we thought it would!

Sent via Ham radio

A sea passage is like a slice of life; sometimes it sucks, other times it's glorious. We've had two nights of squally sideways rain and two days of perfect trade wind sailing. At the moment it's a post-card perfection of 4 to 6 knots downwind. As before on passage, Jim and I are like ships in the night, sleeping and standing watches 4 hours on and 4 off. There's plenty of time to think. Passagemaking isn't always fun; in fact it's more often tiring and difficult. At least most of our passages so far have been tiring and at times quite difficult. But it forces you into the present tense, as I've said before. Somehow the boat's ceaseless motion manages to toss out all the extraneous noise and clutter in my mind, the endless loops of critique, opinion and perspective, stuff that keeps me out of the singular newness of the current moment. Around day 3 it's just me and my internal terrain contemplating sky-blue questions on a spectacular morning that makes the tiresome night squalls fade like bad dreams. It's hard to find this state of mind so quickly anywhere else.

The at-sea visual: a maritime color palette with as many blues as Ireland has greens; The tactile: a cool breeze on the skin, to be savored before it melts into the day's heat; The memory: wondering what friends are doing right this minute and wishing I could call them; The amazement: look at how well this little champ of a boat is sailing!

We needed a real trade wind passage to restore our faith that it's not always a matter of tooth-and-claw for every mile gained, which was how the crossing of the Pacific felt far too often. So far, this passage is delivering on the promise. Our trade wind sail rig is a combination of reefed mainsail let way out and held with a preventer, plus staysail sheeted in fairly tight, and genoa. Right now the genoa is poled out to windward, but we also use it in standard configuration when broad or beam-reaching, both of which we've done on this passage. The great thing about this arrangement is that when a squall hits you just reef or roll in the genoa like a windowshade, leaving the staysail to give the boat power forward. It has worked so well we often haven't had to adjust the steering vane, either. We've toyed with the idea of poling the staysail out to leeward, but it seems to be playing an anti-roll function when sheeted in tight, and neither of the other sails is affected by its presence in the middle.

At times like this I get one of those Holy Crap, willya look at this! moments. I stare at the sails, the rig, the wind vane, the sparkling sea; I think back to all the preparation and hard work to make this happen, and then it hits me with a big smile: It's working! Just as we thought it would!

Sent via Ham radio

Friday, June 1, 2012

Cannibal Tales

We're anchored in the tiny main harbor on the island of Ua Pou in French Polynesia, waiting for steady winds for the next leg.

Below is a mountain view of Taiohae Bay on Nuku Hiva, where this story begins.

There have been enough calms over the past week to make the 600-mile leg to the Tuamotus much longer than necessary (a weather router had said we'd have two days of motoring.) But steady winds will be here by the weekend, and we plan to leave the Marquesas on Saturday (tomorrow.) This rather long, words-only post is being sent via Ham radio, so there are no photos.

UPDATE JUNE 11: Photos have been added.

Warning: Graphic descriptions are contained in this post.

It began innocently enough—a few cruising boat crews going on a tour of the island of Nuku Hiva, with a guide and his assistant to interpret the island's history, flora and fauna. We eight sailors crammed ourselves into two SUVs.

It's hard to know where to start on this subject, a paradox of gentleness and violence, because I didn't grow up thinking about such things. Cannibals in stories were usually caricatures (remember those tasteless cartoons of dogbone-nosed natives with their cooking pots?) I had previously dismissed the topic as a historical curiosity about a distant place where no one alive knows anything firsthand. That assumption was wrong. Now we are in the southern hemisphere, in an island group with not just a known history of human sacrifice and consumption, but also the rap of being the last holdout of cannibalism until the 1950s, possibly later.

We are meeting people whose grandparents, and possibly parents, knew (or know) the taste of human flesh, and the stories and cultural significances of eating "long pig." These elders obviously described it in detail to their offspring, a few of whom seem happy in turn to describe it to us. When you ask questions, answers come at you pretty directly, sort of sinking into your bones with a shudder before you realize it.

As if to emphasize that fact and the old "You're not in Kansas anymore" feeling, a longtime cruising sailor we met reported being out hiking near Anaho Bay two weeks ago and coming across human hand and foot bones. They could be very old bones, but the find implied that if a casual hike turns up that kind of thing, maybe the island's chock full of human bones. He didn't touch them. I asked, "Did you report them to anyone?" He answered, "Nobody'd do anything if I did." Curious.

Here's the deal: Marquesans once numbered around a hundred thousand people splintered into warring tribes and scattered across a handful of small South Pacific islands, in a hundred-mile radius of one another. They've lived here for several thousand years, somewhat isolated in an "end-of-the-line" part of the trade wind world, where from Tahiti and places west it's a long hard upwind paddle in an outrigger canoe to get there. Most visitors came by sail from the Americas (and many still do.) The date of first contact with whites was in the last few hundred years. White men's diseases took their usual toll. Most of the Marquesan culture was wiped out along with all but a couple thousand of their people, so when you look at petroglyphs in a sacred site less than a mile from a currently occupied village, you'll learn that no one knows what they mean. Marquesans have been rebuilding their culture over the past few decades and are fiercely proud of their canoes and the men who race them, their dances, their songs, their historic stone sites, their art, food, language ("We don't speak French, we speak MARQUESAN!") and especially their tattoos. Below are patterns for tattoos, from a museum.

Tattooing here is high art and heavily symbolic. This is an historic sketch of a partially tattooed Marquesan warrior. It took many years to achieve a full-body tattoo.

In spite of the tribal resurgence, Marquesans are mostly Christian, the majority being devout Catholic after heavy missionary influence. The juxtaposition of white Christian crosses on hillsides overlooking harbors with stone structures in jungled valleys where human sacrifices were made is part of the paradox. What shines through the competing historical contexts are the Marquesans themselves, a warm and friendly people who beam back at you, especially when greeted in their own language: Ka-OH-Ha! Here's a canoe race photo-finish going right past us in Taiohae Bay.

It's good to see people reclaiming their customs and culture, but the truths about the more grisly side are there, too. The paradox comes when a Marquesan tells you hair-raising stories about their history of human sacrifice and you see the expression with which he tells it—a puzzling mix of nonchalance and cultural pride. I wondered how someone born here might feel about cannibalism being practiced by their recent ancestors; I found that no shame or embarrassment was evident anywhere; in fact, there is pride that hints of a reclaimed heritage and a ragged fierceness just beneath the surface. The missionaries must have found the "body and blood" sacrament to be the only easy sell in an otherwise culturally repressive imposition of western values that all but eliminated dancing, singing, tattooing, and other things held dear by Marquesans.

We're standing in the middle of a grassy playing field halfway up a mountain, surrounded by dense wet rainforest. Bordered by black basalt boulders, it's a bright green swale about a hundred feet wide by about four hundred feet long. Carved stone tikis, huge stone phalluses (the Marquesan name for their islands is Fenua Enata, or "Land of Men") and other stone forms dot the perimeter, perched on the low wall of basalt blocks. A low wall of red rock is at the far end, and a pa'e pa'e, or 30 by 30 foot square platform about 8 feet high, made of fitted stones, towers over what would be the fifty yard line.

On the far side of the large pa'e pa'e (pronounced "pie-pie") are two red stone statues, both recent re-creations. One statue, the guide told us, is of a priest sacrificing an infant, whose head is pulled back and throat cut. It's a shocking thing to look at. Although infanticide was practiced in some areas for population control, this statue implies ritualized sacrifice, and it stunned me into silence.

The other statue is of a priest marrying a couple who are sitting on skulls. Its meaning is unclear to me. The significance of red stones, all of which were carried up the mountain from a distant sea-level site, is tabu: only priests and high-status people can touch or even walk across a row of red stone. Below is the Catholic church in Taipi Vai, with a row of the same kind of red stone at the altar, but of course everyone crosses it now.

Stones around the tall front edge of the big pa'e pa'e overlooking the arena have a series of small, drinking glass-sized holes in them, obviously for containing liquid. We were told that many were used for tattoo ink, which was made of the burnt ashes of the candle-nut mixed with water and applied to skin with hammer and bone needles. Tattooing is still a painful process, even with modern sterile tools; with the old implements it was excruciating, especially on the face. Even eyelids were tattooed, giving the eyes a huge, popping aspect in the dark background. Old people's skin eventually turned green as a result of the tattoo ink aging. Perhaps the holes in these stones were used for tattoo ink, but there are so many of them at the high altar in this place of human sacrifice that I suspect ink wasn't all they contained. Here are pa'e pa'es midway between the playing field and the top of the site.

The preparation of a human sacrifice involved some degree of torture, to find out the amount of bravery the person being sacrificed possessed. The braver they were, the more honor they were given after they were killed. I don't know what the old ways of torture might have been because our guide, a strapping twenty-something Marquesan who is married and has two small children, did not know. But he told us how the rivalry in his grade school between the white students (who always got the best grades) and the native students often spilled over into ritualized chronic violence.

"We were very violent when we were young boys," said our guide. "For example, my friends and I would wait for one of the kids we didn't like, who'd been nasty to us, and ambush him. We'd throw a sack over his head, carry him off, and tie him still inside the sack to a post that we had stuck into a fire ant hill. Then we'd put a circle of kapok (a cottony substance that grows naturally) around him, and while the fire ants crawled over him and he cried like a baby, we'd set fire to the kapok ring and dance around the fire. Usually the next morning the teacher would say So-and-So will not be in school today." He smiled, admitting, "We were very cruel, but it happens, growing up here."

We're wandering across the playing field, where sports events that involved mostly fighting, including on stilts, were held. He walks over to a small, low pa'e p'ae directly across from the tall pa'e pa'e. It's about 3 feet high, with a 4 foot deep, coffin-sized hole in the middle. "Human bones were thrown in that hole after people finished with them," he said. Eventually the bones were used for fish hooks, carvings and other things. Not long ago when this site was restored, the archaeologists found a French soldier in there from the 1700s, complete with a musket and a tricorn hat. Evidently the French had used this site as a burial ground.

On this low pa'e pa'e's front wall sits a 3-foot wide stone with a curved, sharp, half-rounded inside edge. "This is the stone where the heads were cut off," said the guide. In use, it rested with the curve side up.

You could see where the victim's neck went. He continued, "If the person being sacrificed still wasn't dead by the time he was to have his head cut off, meaning he was very brave and strong, there was a tool used to break the neck." He demonstrated by pretending to hold a lever. Later I saw one of these tools, in Rose Corser's museum in Taiohae. It looks like a wooden war club, elaborately carved, with a thick, Y-shaped wedge at the end sporting a neck-sized, curved inside surface. It was chillingly easy to see how quickly such a tool could do its work.

"Once the head was cut off," said our guide, "It was carried over to the chief up on the platform. He would eat the eyes for good vision and the brain for intelligence." Raw or cooked, it didn't matter (I asked.) He then made a joke about other rival tribes such as Tahitians, eating the genitalia for good sex. I had heard this joke once before. Evidently this is a huge inside put-down.

"In order to keep the spirits of the people who were sacrificed, and who were probably very angry about it, from coming back to harm the tribe, they cut off the person's hands and feet," said our guide.

"So these people were afraid of the angry spirits from the people they sacrificed and ate?" I asked.

"Oh yes," he said.

We're standing in a jungle of trees above the playing field. Large black stones are laid steplike up the steep slope. The stones have many flat surfaces, but the Marquesans say they were all fitted from natural shapes—even more amazing than if they'd been cut. There are literally miles of fitted stone structures on these islands. The stone is a weathered form of columnar basalt that naturally has edges and flat surfaces. Only the red stones, most of different origin, were cut. Here is a section of this partly-restored slope. That's our guide's assistant.

"So, if they were afraid of the angry spirits coming back," I continued, "is that not some kind of collective admission that they knew eating human flesh was (I didn't want to say the word 'wrong') …um, not going to sit well with the people they ate?" But he changed the subject. On later reflection, I don't think this knowledge that victims' spirits were royally pissed off can be judged as evidence of anything—it's just the way things were, and me questioning it through the lens of my western eyes felt irrelevant in the context of where I was standing at the time.

I began reading Herman Melville's book Typee while anchored in a bay called Hanga Haa in front of the Taipi Vai valley, where he lived for a few months after escaping from a brutal life aboard the whaler Acushnet. He lived among the Typees, a tribe with a fierce reputation, and one of the last to succeed in repulsing the French Navy. The book gave me some historical perspective. Though told from a western viewpoint in novelized form, Typee is an account of a true event. Here are some photos of Taipi Vai, or the Typee Valley. In the first, we're sailing into its spacious bay.

This is Taipi Vai viewed from up on the mountain:

This is the view looking seaward from the mountain:

During the middle part of his captivity, Melville's prose indicates that he might have experienced a mild form of Stockholm Syndrome. While he knew some Typees were cannibals, he hadn't seen any "enormities" or evidence of cannibalism. In fact, there was evidence aplenty, as he was horrified to later find. Three shrunken heads (two Marquesan and one White) concealed in white tapa cloth, had been hanging over his bed the whole time he'd been there. In spite of this and catching sight of a box containing fresh, wet skeletal remains of a human corpse after a battle with the nearby Happar tribe, in which several captives disappeared, his remarks remained sympathetic.

He says: "…it will be urged that these shocking unprincipled wretches are cannibals. Very true; and a rather bad trait in their character it must be allowed. But they are such only when they seek to gratify the passion of revenge upon their enemies; and I ask whether the mere eating of human flesh so very far exceeds in barbarity that custom which only a few years since was practiced in enlightened England: a convicted traitor, perhaps a man found guilty of honesty, patriotism and suchlike crimes, had his head lopped off with a huge axe, his bowels dragged out and thrown into a fire; while his body, carved into four quarters, was with his head exposed upon pikes, and permitted to rot and fester among the public haunts of men!"

Human sacrifices were most likely to be members of nearby rival tribes, though this does not fully explain infanticide. There were tribes in every valley, including Taiohae, Taipi Vai, and in the area now called Daniel's Bay. They all made raids upon each other, and guarded their borders along high mountain ridges. The German tourist who disappeared last year and whose charred bones were found in a fire had been on a cruising boat anchored in Daniel's Bay, with his girlfriend. Our guide personally knew the man who is accused of killing him. "I grew up with him, he would never do a thing like that," said our guide, who'd been shocked at the news. "You don't kill a person who's not your enemy."

Did they somehow become enemies? When the girlfriend went in search of her mate, the perp assaulted her, tied her to a tree and left her. She escaped. The incident is widely disavowed and the accused man is publicly regarded as crazy.

Which brings us to the paradox. While violence from ancient enmity from a host of different sources continues into our own time, told as stories in the nightly news interspersed with soap commercials, questions about cannibalism reach to the heart of exactly what is forbidden and what is sacred to a society.

Okay, I thought, as we walked along thousand year-old stone paths; so they only killed and ate their enemies, and the statue over there indicates they practiced infanticide. These impressions combined with Melville's account say there appears to have been some degree of restraint—right?

Our guide's next utterance destroyed that idea. "In fact, though, it was common practice to club someone else's child if nobody was watching," he said.

I could hardly believe my ears.

"A mother might send her kid out to gather taro, and the kid would never be seen again." His expression indicated that he knew this would shock us. I was beginning to wonder if he was pulling our tender legs.

"All you had to do was hit 'em once with a club and bury them in a luau pit," he said. "The body cooks underground and there's no evidence because nobody can find it." Then he added, "Some of the Old Ones say people used to love sucking on those little finger bones!" He smiled.

Now seriously. Is he putting us on? Maybe there were differences from tribe to tribe. With the isolation it's possible—we have towns that are as night and day to each other, even though geographically proximate. Melville's account shows no knowledge of this practice among the Typees. There's no reason to doubt that behavior varied from tribe to tribe, or person to person, just as it does today. But I'm creeped out from head to toe.

We climbed through rock ruins up a hill to where a gigantic banyan tree stood atop the biggest pa'e pa'e of all.

It was planted 500 years ago, and our guide said it had something to do with a big hole on the other side. Curious, I wandered in light rain over to the back side of the tree, away from the small group of cruising sailors. I figured, trees are good, right? There was a curious rock structure behind the tree and under its copious roots, so I called out a question to him. He looked alarmed. Motioning with his arm, he shouted, "Come here!" Whoops, I thought, maybe I wasn't supposed to see whatever it is I've seen; it was just a row of stones. Here's another view of it, right atop the high altar.

I stuck close to the guide as we traipsed up the hill past the banyan, into more sacred ground where only the highest priests could go. There was a small pa'e pa'e up there, where they once lived. Our guide muttered and chanted some phrases in Marquesan, and gestured brusquely with his arms off to his sides, as if brushing things away. His assistant, who brought up the rear of our small group, answered in a call-and-response way as we passed the tree, which I assumed was related to what our guide in the front was doing. We walked up the hill, arriving at a richly petroglyphed set of rocks showing fish, a whale, turtles, humans, and other things, but their meanings have been lost in the mist of time.

Later on I quietly asked him, "Are there still sites here on the island that are tabu?"

"Oh yes," he said. "Many more sites in the forest that haven't been restored are tabu. Many sites are not even known to outsiders, and are still full of spirits. Those sites are tabu."

"Is this site tabu?" I said.

"No, we did an exorcism," he said. So that's what the two Marquesans were doing as we went up the hill past that tree, I thought.

We descended to the back side of the banyan tree. A stone-lined round hole about ten feet wide and at least twenty feet deep was where captives were kept before being killed, and we gazed uncomfortably into it. Tree roots twined into the deep hole, weaving a ropy tangle at the bottom. Our guide is standing at its edge in this photo.

The misery welling out of that hole in black waves of silence felt overpowering, so I walked away from it and the group again. But I heard someone asking how victims were cooked, and thought, good god, a recipe's coming. Our guide cheerfully supplied the answer. He said there were different ways; in one way, the body was hoisted upside down and the skin flayed off the legs, "covering everyone in grease," he added. "Some people developed a real taste for it."

I clearly had the feeling that this guide was giving us more information than he gave most tours; in part because we women had been curious early on, asking lots of questions about plants and animals and general island history in the car, and in part because he became visibly more relaxed with us as the day wore on. I would think if a tour like this was a standard item, we might have heard of it along the cruising boat grapevine.

As we rode in his car on the narrow mountain road, he described the common practice of killing and eating one of the island's many pigs, which is a family event: "First you cut the throat and hang it up quickly so you can catch all the blood." Then he turned to the women in the Toyota's back seat and grinned, showing his big teeth. "We LOVE eating the blood! We put it in the fridge so we can use it later." A couple days later, two of us remarked on this leer seeming a bit gratuitous. The general shock value of the tour's non-botanical components made it hard to distinguish how much enjoyment he was getting from our white-bread reactions, so it's impossible for me to say if any exaggeration was being employed. I have no reason to assume it was.

I tuned out the rest of his talk. Seeing the relish with which he described eating the blood made me think, we're hearing about a pig… right? But it wasn't hard to make the mental leap, because he made it easy to imagine. Perhaps we got the insider's cannibal tour most people don't get, or perhaps not. Maybe some Marquesans would disagree with his statements, and maybe not. He obviously wanted us to know, really know at a gut level, what happened here, and how some descendants of the grandmothers and grandfathers who also happened to be cannibals, feel about it.

On the island of Ua Pou yesterday, Jim and I went for a drive with a friendly local Frenchman who's lived here since 1996. After a jolting ride over unpaved mountain roads, we reached an exceptionally well-restored stone ceremonial center with an L-shaped playing field, similar in dimensions except for the L-shape, to the one at Nuku Hiva.

Each end had a 6 foot wide, table-sized flat rock perched on smaller stones. "This is where they cut off the heads," said Xavier, as casually as someone in a grocery store might say, this aisle is where you can find the vegetables.

These are the living quarters around the playing field. Sleeping mats are in the back.

Here are some thatch details. The sides were steep to shed rain, and doorways were low.

A few miles later, we saw a stone pa'e pa'e that's been converted into a piggery. The inner stones are gone and it's just a square stone enclosure near a beach. Seven large pigs rooted through the coconut husks, trapped in their little enclosure, as the surf pounded on the shore just out of sight.

This is Xavier, our French guide at Ua Pou, with Jim at a cliff on Ua Pou's beautiful east side. He swims out to the anchored boats each day, chatting and getting to know the cruising sailors.

Again, here's Hermann Melville, with the mid-nineteenth century context: "But here, Truth, who loves to be centrally located, is again found between the two extremes; for cannibalism to a certain moderate extent is practiced among several of the primitive tribes in the Pacific, but it is upon the bodies of slain enemies alone, and horrible and fearful as the custom is, immeasurably as it is to be abhorred and condemned, still I assert that those who indulge in it are in other respects humane and virtuous."

Sent via Ham radio

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)